How Literature and Music Converged in Hoffman and Schumann

As a student majoring in both music and computer science, I’ve always believed that different disciplines share deep, intrinsic connections. Even today, as technology continues to reshape our world, great products are still rooted in art, culture, and human sensibility. This idea becomes even more vivid when we look back at the Romantic era — a time when the ties between music and literature were especially strong.

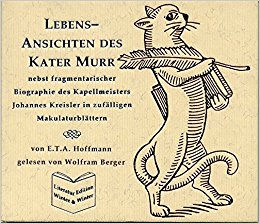

Robert Schumann and E.T.A. Hoffmann were two of the 19th century's most fascinating figures. Though there's no historical proof they knew each other personally, their artistic spirits were undeniably aligned. Both rebelled against the middle-class complacency of the Biedermeier era and fought for deeper, more imaginative forms of art. Schumann’s Kreisleriana was directly inspired by Hoffmann’s literary character Johannes Kreisler, from The Life and Opinions of the Tomcat Murr. By comparing these two works, we can see striking parallels in three key areas: Style, Unusual Form, and Spiritual Vision.

🎨 Style

Both Schumann and Hoffmann broke with tradition and pioneered new aesthetic styles. In the post-Classical period, composers like Beethoven and Schubert had already begun exploring more emotional, personal expressions. Then came the Sturm und Drang movement, a turning point where art moved from mere entertainment toward raw, expressive content.

In Kater Murr, Hoffmann's portrayal of Kreisler is intensely emotional and spontaneous. For instance, in a scene where Princess Hedwiga and Julia encounter the stranger (Kreisler), his bizarre behavior rapidly swings the mood from curious to terrified. Dialogue like “Suddenly the stranger’s face transformed itself again into that ludicrous mask...” shows rapid emotional shifts and a dramatic, almost chaotic tone. Kreisler speaks in bursts of thought, almost like stream-of-consciousness, often peppered with foreign words like “Kakodämon” (Greek for devil), “ex abrupto” (Latin for suddenly), and “che far, che dir!” (Italian for “what to do, what to say!”) — evidence of a scattered, expressive mind.

Schumann mirrors this energy in Kreisleriana, particularly in the first movement (Op. 16 No. 1), marked Äußerst bewegt ("extremely agitated"). The opening is packed with accent marks, dynamic shifts, and changing rhythmic groupings — a musical equivalent of Kreisler's rapid, emotional speech.

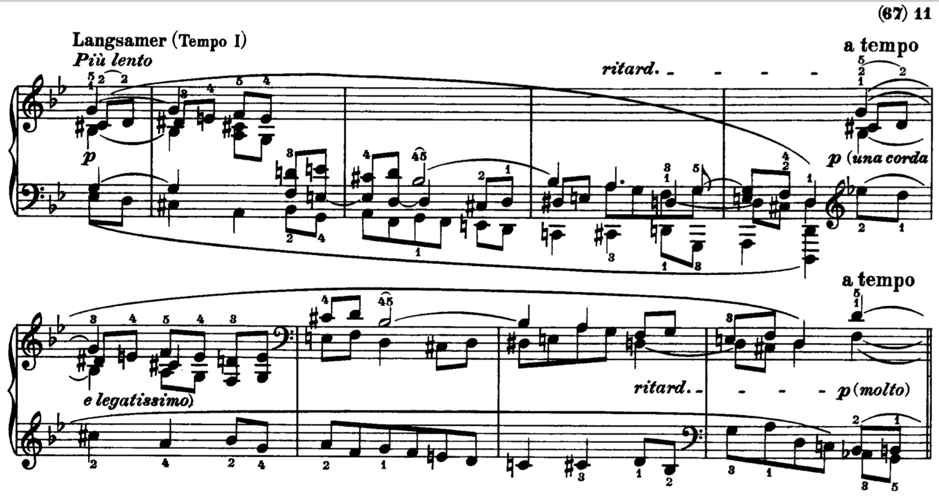

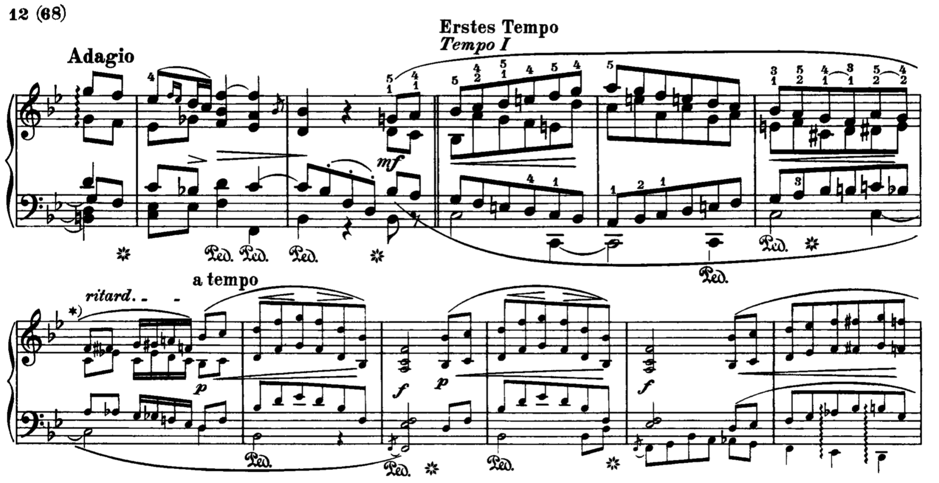

Later, in No. 2, Schumann introduces rich chromaticism and complex left-hand figurations far beyond Classical norms. For example, in Intermezzo II, the chromaticism and sweeping motion evoke a turbulent emotional state:

Near the end of No. 2, he even integrates contrapuntal techniques reminiscent of Bach:

Just as Hoffmann references literary giants like Shakespeare, Schumann may be drawing from musical forebears like Bach — both artists grounding their avant-garde work in tradition. In contrast to the shallow entertainment of Biedermeier art (as mocked in Kapellmeister Johannes Kreisler's Musical Sufferings), Schumann’s technical complexity seems to say: this is serious art — elite, thoughtful, and worthy of deep attention.

🧩 Unusual Form

Another striking parallel between these works is their structural innovation.

In Kater Murr, the cat writes his autobiography on the backs of Kreisler’s manuscripts, creating a fragmented narrative. The book jumps unpredictably between the two stories, marked by abbreviations like “s.p.” and “M.c.” For instance, just as Murr starts a thought — “However, in considering…” — Hoffmann abruptly shifts to Kreisler. Or later, just when Benzon begins to explain something important to Princess Hedwiga (“In two words...”), Hoffmann interrupts again.

This abrupt, collage-like structure is echoed in Kreisleriana, where Schumann shifts dramatically between contrasting moods and tempi across its eight movements:

- Äußerst bewegt – extremely agitated

- Sehr innig und nicht zu rasch – very heartfelt and not too fast

- Sehr aufgeregt – very excited

- Sehr langsam – very slow

- Sehr lebhaft – very lively

- Sehr langsam – very slow

- Sehr rasch – very fast

- Schnell und spielend – fast and playful

Each section feels like a sudden turn in a story. The tonal layout is equally dynamic, frequently alternating between D minor and B-flat major. This oscillation mirrors the duality in Hoffmann’s characters — the sensitive and melancholic Kreisler vs. the simple, joyful Murr.

One powerful example is the jump from No. 7 to No. 8. No. 7 ends slowly, while No. 8 begins Vivace e scherzando — quick and playful, almost as if Murr himself has leapt into the music. It’s tempting to imagine a hidden “M.c.” buried between the lines of the score.

🌌 Spiritual Connection

Beyond style and structure, what truly binds Schumann and Hoffmann is their shared Romantic spirit — passionate, imaginative, and elite in vision.

Hoffmann’s writing gave Schumann more than just creative inspiration — it offered emotional validation. Kreisler, the tormented genius, often laments the state of art. On page 65, he cries:

“Through the vacuous, childish playing with sacred art... through the idiocies of the soulless dabblers in art... I came to recognize the wretched uselessness of my existence.”

Schumann, like Kreisler, struggled against mediocrity and philistinism in the music world. By portraying Kreisler, Schumann was really portraying himself — using fiction to express personal truths.

Hoffmann’s bold literary form and emotional freedom may also have encouraged Schumann to break conventional musical rules and embrace eccentricity. With Hoffmann paving the way, Schumann had license to create something radically new.

A modern parallel? Think of how Steve Jobs was inspired by the Beatles’ psychedelic experiments — wild, creative works that helped spark the invention of bold, visionary products.